What Is the Science of Weight Loss?

Body mass index (BMI) is used as a universal estimate of “health” and is the product of a person’s weight and height. BMI is calculated as: body weight (kg)/height (m)2

On a continuum scale, the following estimates are used to categorize people from being underweight through to being obese:

The world health organization (WHO) defines obesity as excessive fat accumulation that might impair health and is diagnosed at a BMI of ≥30kg/m2. Recent global evidence suggests that more than 1.9 billion adults worldwide are overweight and 650 million are obese, while approximately 2.8 million deaths are due to being overweight or obese. In India alone, more than 135 million individuals are considered to be obese.

Obesity is a serious health concern as it substantially increases the risk of metabolic diseases (type-2 diabetes mellitus and fatty liver disease), cardiovascular diseases (hypertension, myocardial infarction, and stroke), musculoskeletal disease (osteoarthritis), Alzheimer disease, depression, and some types of cancer (breast, ovarian, prostate, liver, kidney, and colon). Obesity may also lead to reduced quality of life, lower productivity and various social disadvantages. In 2020-21, as the novel SARS-COVID-19 pandemic spread, the risk of contracting the virus and being hospitalized was significantly increased in people who were obese.

What is weight loss and why is it so important?

Before we can cover healthy weight loss strategies, we must first understand what the term “body weight” refers to. We can define it as the sum weight of your bones, muscles, organs, blood, fat etc. Thus, when one stands on a set of scales, the number on the screen represents everything within their body, respectively.

Therefore, using scales can often be fraught with some danger as any “lost weight” on the screen tells us that one or more of the components comprising one’s sum weight (i.e., muscle, organ, blood, fluid, fat, etc.) have changed. Ideally, we would like all weight loss to come from body fat reductions. However, the scales are unable to differentiate, so weight loss may come from either fluid, waste, or even muscle losses.

Why is fat loss better than muscle loss?

Lean muscle (or otherwise known as lean body mass) consists of fat-free and bone mineral-free components that include muscles, skin, tendons, and connective tissues. As such, lean muscle is vital for sustaining physical function and posture. In addition, muscle is responsible for several metabolic processes, including maintaining healthy body organ function and protein metabolism.

Fat, on the other hand, can either be visceral (around internal organs and predominantly found in and around the abdomen) or subcutaneous (fatty deposits found around the body underlying the skin).

Subcutaneous fat accumulation represents the normal physiological buffer for excess energy intake (i.e., high caloric diet) with limited energy expenditure (i.e., physical inactivity). When the storage capacity of subcutaneous fat is exceeded, fat begins to accumulate in areas outside the subcutaneous tissue, such as the visceral fat found in the abdomen for example.

When excess visceral fat around the abdomen increases (in obese individuals), there is a concomitant rise in the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Therefore, it is preferable to lose fat rather than muscle to lower the risk of comorbid conditions associated with obesity, while also increasing the body’s ability to metabolize protein.

What is the science of weight loss?

The general rules for losing weight are

1) engage in regular physical exercise, and

2) restrict (or significantly change) food intake strategies

As far as engaging in regular physical exercise goes, evidence suggests that engaging in greater amounts of physical activity (>250min/week) have been associated with clinically significant weight loss. In addition, individuals should engage in moderate-intensity physical activity between 150min/week-250min/week to be effective to prevent weight gain. On the other hand, moderate-intensity physical activity levels of between 150min/wk-250min/week may improve weight loss in conjunction with dietary restrictions, but not severe diet restriction.

There is no consensus regarding the effectiveness of different modes of exercise training for weight loss, although the accepted practice is undertaking aerobically-based activities (running, cycling, high intensity interval training, swimming, cross training etc.)

Resistance training alone, while useful for improving strength levels, may not yield the same weight loss benefits as aerobic training, as typically, the total energy expenditure is higher during aerobic training.

The following table summarizes the possible effects of different types of training on weight loss.

| Exercise type | Range of expected weight loss | Chance of clinically significant weight loss |

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic exercise training only | 0 to 3% | Possible, but only with high exercise volumes |

| Resistance training only | 0 to 1% | Very unlikely |

| Aerobic + resistance training | 0 to 3% | Possible, but only with high volumes or aerobic exercise training |

| Caloric restriction + aerobic exercise training | 5 to 15% | Possible |

When it comes to restricting (or significantly changing) food intake strategies, there is wide-ranging evidence concerning the amount of restriction, as well as the mode (i.e., diet type) of restriction, needed to facilitate healthy weight loss. Before we dive into the evidence though, it is firstly important to understand some key concepts.

1. What is a calorie? A calorie is a unit of energy defined as the amount of heat needed to raise the temperature of a quantity of water by one degree.

2. What is a kilojoule? A kilojoule is another unit of energy. 1,000 calories are equivalent to 4,180 kilojoules. Food energy quantities (at the back of food packaging for example) are often expressed in kilojoules.

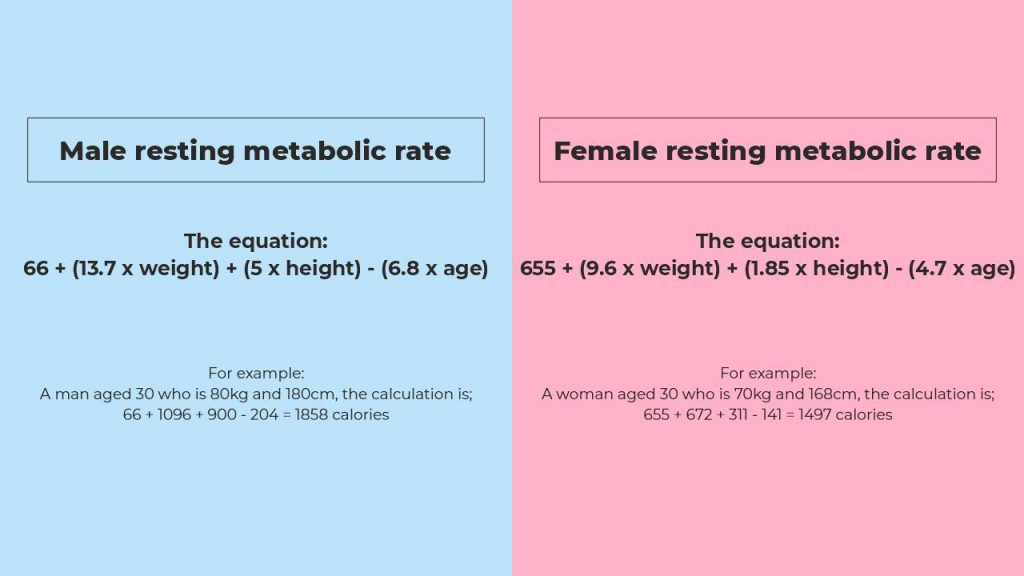

3. What does basal metabolic rate (BMR) mean? The BMR is the number of calories required to keep your body functioning at rest. The equation to establish BMR is different for men and women.

Using the above definitions, a caloric deficit would be restricting the number of calories consumed that are needed to sustain one’s BMR by an arbitrary figure. The anecdotal rule of restricting one’s daily caloric intake by 10% seems an arbitrary figure, as there is no golden rule for restricting caloric intake by “X amount”, which will result in “X amount of fat loss”.

Moreover, it appears that daily calorie restriction is as effective as intermittent calorie restriction (24 hours of ad libitum food consumption alternated with 24 hours of complete or partial food restriction) for weight loss. The question about what is considered safe and effective in terms of various diets (macronutrient intake and timings) remains though.

Also read: Calorie Deficit: How to Calculate It for Weight Loss

Low and very low-calorie diets

Low and very low-calorie diets are represented as 800kcal/ day–1200kcal/ day and 400kcal/ day–800 kcal/day, respectively. Both forms of calorie deficit are thought to trigger rapid losses in weight.

However, some researchers have criticized such weight loss methods due to the possibility of causing losses in lean body mass (muscle). As an adjunct, resistance training implemented alongside low and very low-calorie diets may be useful in sustaining lean muscle mass. Further evidence though, is needed to support the combination of low/ very low-calorie diets and resistance training as an effective weight loss strategy.

Overall, evidence has suggested that for significant and safe weight loss to be achieved, a caloric deficit is required, with a minimum level of approximately 1,200kcal/day for women and approximately 1,500 kcal/day for men

In addition, the consumption of dietary fiber and protein (also known as high-protein, low calorie diet) should be prioritized early on when in a caloric restriction period and may confer some additive weight loss benefits.

Low-fat diets

Low-fat diets have been defined as providing 20%–35% fat, or more specifically a daily intake of protein at 10%–35%, carbohydrate at 45%–65%, and fat at 20%–35% of total energy. Such a macronutrient percentage intake may yield some advantages for weight loss. However, the long-term effects seem poorly understood and it appears that this form of diet is difficult to sustain, due partly to the lack of energy-dense (fatty) foods in the diet.

High-protein diets

An important consideration for weight loss (besides the energy in/ out relationship) is the thermogenic quality of the foods taken in, specifically of the different macronutrients (protein, fats and carbohydrates).

Of the macronutrients, protein has the highest thermic effect and is the most metabolically expensive. Given this, it is not surprising that higher protein intakes have been seen to preserve resting energy expenditure while dieting. In addition, protein is the most satiating macronutrient, thus allowing you to feel fuller for longer after consumption — which is important to prevent overeating. High-protein diets have been identified as ranging from 1.2g/kg–1.6 g/kg, and appears to be an effective strategy for boosting metabolism while protecting against muscle wastage.

Low carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets

Ketogenic diets consist of carbohydrate intake of approximately 50g/day or 10% of total daily energy expenditure. In this sense, total daily calories are not reduced, which helps maintain appetite (hunger), causing spontaneous reductions in energy (kcal) intake under non-calorically restricted conditions. However, this extreme alteration to the daily diet can be difficult to maintain.

Moreover, excluding nutrient dense high-carbohydrate foods, which may have disease-preventive qualities, could be problematic. Lastly, because of the lack of daily carbohydrate intake, there may be difficulties (limitations) experienced in high-intensity training output, which largely relies on energy derived from carbohydrates.

Is rapid weight loss better than gradual weight loss?

Few pieces of evidence exist exploring the utility of rapid weight loss strategies compared to those that aim for sustained, gradual weight loss. However, from the preliminary research, it appears that gradual weight loss (eg, losing 6kg in 12 weeks) offers some benefits over rapid weight loss (eg, losing 12kg in 12 weeks) in terms of greater reductions in body fat percentage and overall fat mass, while preserving healthy resting metabolic rates.

References

1. Ahirwar R, Mondal PR. Prevalence of obesity in India: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2019; 13: 318-21.

2. Popkin BM, Du S, Green WD, et al. Individuals with obesity and COVID‐19: A global perspective on the epidemiology and biological relationships. Obesity Rev 2020; 21(

3. Landi F, Camprubi-Robles M, Bear DE, et al. Muscle loss: the new malnutrition challenge in clinical practice. Clin Nutr 2019; 38: 2113-20.

4. Ibrahim MM. (2010). Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: structural and functional differences. Obesity Rev 2010; 11: 11-18.

5. Donnelly JE., Blair SN, Jakicic, JM, et al. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009; 41: 459-71.

6. Swift, DL, McGee JE, Earnest CP, et al. The Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Weight Loss and Maintenance. Prog Cardiovascular Dis 2018;, 61: 206-13.

7. Ramage S, Farmer A, Apps Eccles KA. Healthy strategies for successful weight loss and weight maintenance: a systematic review. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2014; 39: 1-20.

8. Varady KA. Intermittent versus daily calorie restriction: which diet regimen is more effective for weight loss? Obesity Rev 2011; 12: 593-e601.

9. Willoughby D, Hewlings, S, Kalman D. Body Composition Changes in Weight Loss: Strategies and Supplementation for Maintaining Lean Body Mass, a Brief Review. Nutrients 2018; 10: 1876.

10. Freire R. Scientific evidence of diets for weight loss: Different macronutrient composition, intermittent fasting, and popular diets. Nutrition 2020; 69:110549.

11. Ashtary-Larky D, Bagheri R, Abbasnezhad A, et al. Effects of gradual weight loss v. rapid weight loss on body composition and RMR: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nut 2020; 124: 1121-32.

12. Aragon AA, Schoenfeld BJ, Wildman R, et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: diets and body composition. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2017; 14:16.