Early Signs of Running Injuries and How to Avoid Them

Running is a popular physical activity and its popularity is directly related to its numerous health benefits, which include improved musculoskeletal health, body composition, cardiovascular health, and psychological state. Unfortunately, running is also implicated in high rates of musculoskeletal injuries, with as many as 65% of all runners reporting overuse running injuries each year (Messier et al., 2018).

The low compliance of running on roads, such as asphalt and concrete surfaces, shows higher impact forces when compared to gravel or grass surfaces — ie, the force that travels up the body when the foot hits the ground (Dolenec, Štirn and Strojnik, 2015), which can predispose runners to more overuse injuries (Rolf, 1995).

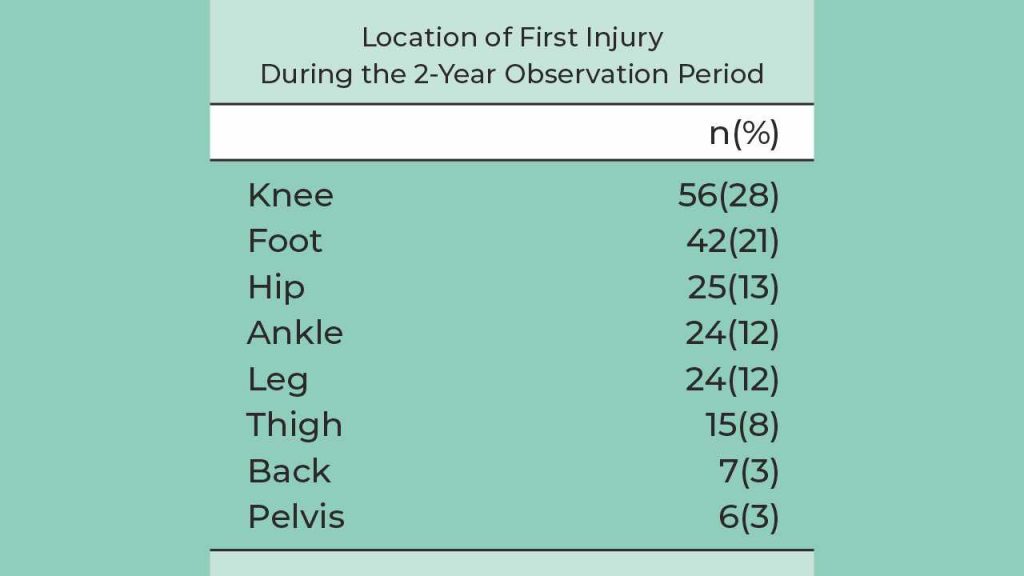

There is also an increased risk of running-related injury due to the cambered nature of roads (OConnor and Hamill, 2002). Runners who run predominantly on road also have a high occurrence of injuries, up to 79% incidence, with a large percentage (28%) of this being of the knee (Taunton et al., 2003; Van Gent et al., 2007), followed by the foot (21%) as shown in table 1 (Messier et al., 2018).

Running injuries: Early signs and preventative measures

Listening to your body is arguably the best method to prevent a slight niggle from becoming a full-blown injury. Following this will facilitate injury prevention in sports. Injury determinants are multifactorial, and can be many factors, such as biomechanics of running, increasing load too quickly, level of previous training, as well as emotional and lifestyle stressors such as anxiety and work/ academic stress (Gabbett 2019).

Many studies have been done to determine how to prevent injuries, and approaches such as wearing more cushioned running shoes, or using a warm-up and cool-down showed no effect in the incidence of running-related injuries (Fokkema 2017).

Often, an injury will begin to show up as a minor pain, or ‘niggle’. For example, you may find that you have a slight pain on the tip of your knee cap when you descend stairs. This is usually an indication that something is wrong, and should be addressed immediately. However, by the time it is addressed, it is usually too late and the knee injury after running is at a stage where it needs to be addressed by seeing a physiotherapist and a rehabilitation process, which often involves less to no running.

Many factors are shown to increase the risk of running-related injuries. Factors such as:

- having a history of previous injuries

- advancing age

- sudden increase in intensity, duration and frequency of training

- not warming up before training

- wearing improper shoes

- not incorporating rest/recovery days in training schedule

- poor biomechanics

Also read: Hot Pack vs Cold Pack: What’s Best for a Running Injury?

The overarching rule is: If you feel like something is wrong, then it probably is. A muscle or ligament tear is very easy to notice. You would generally do a movement that is unusual, such as a twisted ankle, or a twist in the knee, followed by a sharp pain in the area. If you hear a loud “pop”, then you have likely tore something. The general rule is that if there is immediate swelling followed by bruising in the area the following day, then you have caused damage, which needs to be assessed.

What to do to reduce the risk of injury?

- Start off your running program slowly, and gradually increase each week (this should be done by a coach)

- Focus on decreasing your body weight by sticking to a strict diet, if necessary

- Run between 2-4 ties per week at the start

- Run with a higher cadence of roughly 90 steps per minute

- Stretch after each session, with specific focus on the legs

- Shift to a more midfoot or forefoot striking pattern over time

- Run some of your training sessions on grass or gravel roads to reduce the impact

Also read: How to Train Safely and Avoid Injuries at Home

This is why working with a professional or a coach is an absolutely critical aspect of your running training plan, particularly if you are just starting out. A coach can guide you on correctly increasing your training load, and keep those injuries at bay.

References

1. Dolenec A, Štirn I, Strojnik V. Activation Pattern of Lower Leg Muscles in Running on Asphalt, Gravel and Grass. Coll Antropol 2015; 39: 167-72.

2. Gabbett TJ. Debunking the myths about training load, injury and performance: empirical evidence, hot topics and recommendations for practitioners. Br J Sports Med 2020; 54: 58-66.

3. Messier SP, Martin DF, Mihalko SL, et al. A 2-Year Prospective Cohort Study of Overuse Running Injuries: The Runners and Injury Longitudinal Study (TRAILS). Am J Sports Med 2018; 46: 2211-21.

4. Rolf C. Overuse injuries of the lower extremity in runners. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1995; 5: 181–190.

5. Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, et al. A prospective study of running injuries: the Vancouver Sun Run “In Training” clinics. Br J Sports Med 2003; 37:239–44.

6. van Gent R, Siem D, Middlekoop M, et al. Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: a systematic review, Br J Sports Med 2007; 41:469–80.