Science of Progression in Resistance Training

The benefits of resistance training are well documented in scientific literature. It is one of the most effective means to improve power, speed, hypertrophy, strength, muscular endurance, balance, and coordination. Hence, its popularity in all sports, and it being recommended by health organizations such as the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Foundation in the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases.

Periodization and progression are two vital components of training to bring physiological and psychological adaptations, and progress towards your goals. Periodization is the logical and sequential manipulation of training variables, such as intensity and volume of training. Planned periodization and progression is what helps in reducing the risk of injuries, improving performance, and preventing overtraining.

Also read: How to Stay Consistent in Your Training

Fundamental aspects of progression

The goal of any resistance training workout program is to improve a certain component or multiple components of performance. For these improvements to occur, the program must be designed in such a way that it challenges the limits of the body and adapts to the altered stimulus.

Progression is the systematic and sequential process of moving forward toward a set goal

It is a fact that the same rate of improvement cannot be sustained for a long period of time, however careful planning of variables of training limit plateaus (where no improvements take place) ensures improvement in performance.

The three fundamental principles of progression are:

- Progressive overload

- Specificity

- Variation

Progressive overload

This is a planned and systematic increment in the loads placed on the body during training. Adaptation in the human body occurs only when it is repeatedly forced to greater levels of stress to meet higher demands of training.

Now, there are numerous ways in which you can apply this principle to your training:

- Increasing the resistance

- Adding more repetitions to the current load

- Modifying repetitions speed with submaximal loads

- Shorter rest periods

- Increase in total volume

- Or any combination of all these variables

By improving your motor unit recruitment, firing rate, and synchronization, your nervous system plays a crucial role in the improvement in the early stages of training. Now, for further improvements in neural adaptation to take place, a progressively greater amount of load is to be applied. This progressive overload is crucial for maximal muscle fiber recruitment and, consequently, muscle fiber hypertrophy and strength increase, improvement in power, and local muscular endurance. Hence, it is crucial to have the element of progressive overload in your regime.

Specificity

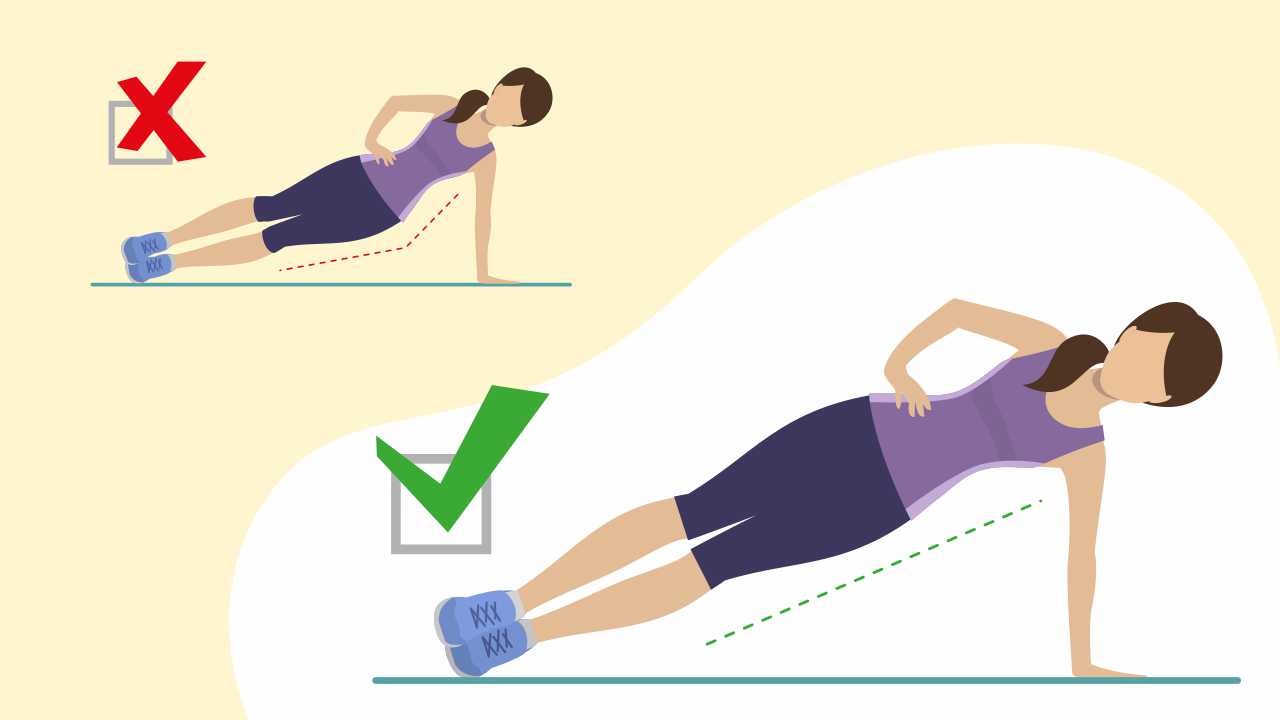

This principle states that specific stimuli and movement patterns bring about specific adaptation — so, if your goal is to improve your maximal strength, your training load or stimulus should mimic the demands specific to your goal.

The physiological adaptations to training are specific to:

- Muscle actions involved

- Speed of movement

- Range of motion

- Muscle groups trained

- Energy systems involved

- Intensity and volume of training

This high degree of specificity between movement patterns and the adaptations to force-velocity characteristics make specificity an integral part of training. So, ensure that your training matches the needs and demands of your desired goal/s.

Variation

This requires manipulation of one or more training variables over time, so that the training stimulus remains optimal. Systematic variation of volume and intensity of training is stated as the most effective way to apply variation in training.

Training variation, also termed as periodisation, states that adaptation occurs in three stages:

- Shock: Immediate response to a training stimulus

- Adaptation: In the second stage, performance improves, and adaptation to a stimulus occurs. At this point, the stimulus needs to be altered or no adaptation will take place

- Staleness: The third stage brings stagnation in performance improvements

Periodized programs are superior to non-periodized programs and are not limited to just athletes. Recreational athletes and fitness enthusiasts can benefit just as much.

Periodization models

Classic model

This model involves high initial volume at low intensities, and as training progresses, volume decreases with a simultaneous increase in intensity.

Undulating model

It is characterised by variation in training intensity and volume within the seven to 10-day cycle. However, in a single session, only one characteristic is trained. One example of rotation in this program is:

- Day 1: 3 – 5 RM loads

- Day 2: 8 – 10 RM load

- Day 3: 12 – 15 RM loads

Research indicates this model to be superior in improving 1-RM strength over a period of 12 weeks.

Guidelines for strength, hypertrophy, endurance and power training — few common variables

- Perform eccentric and concentric work in your training

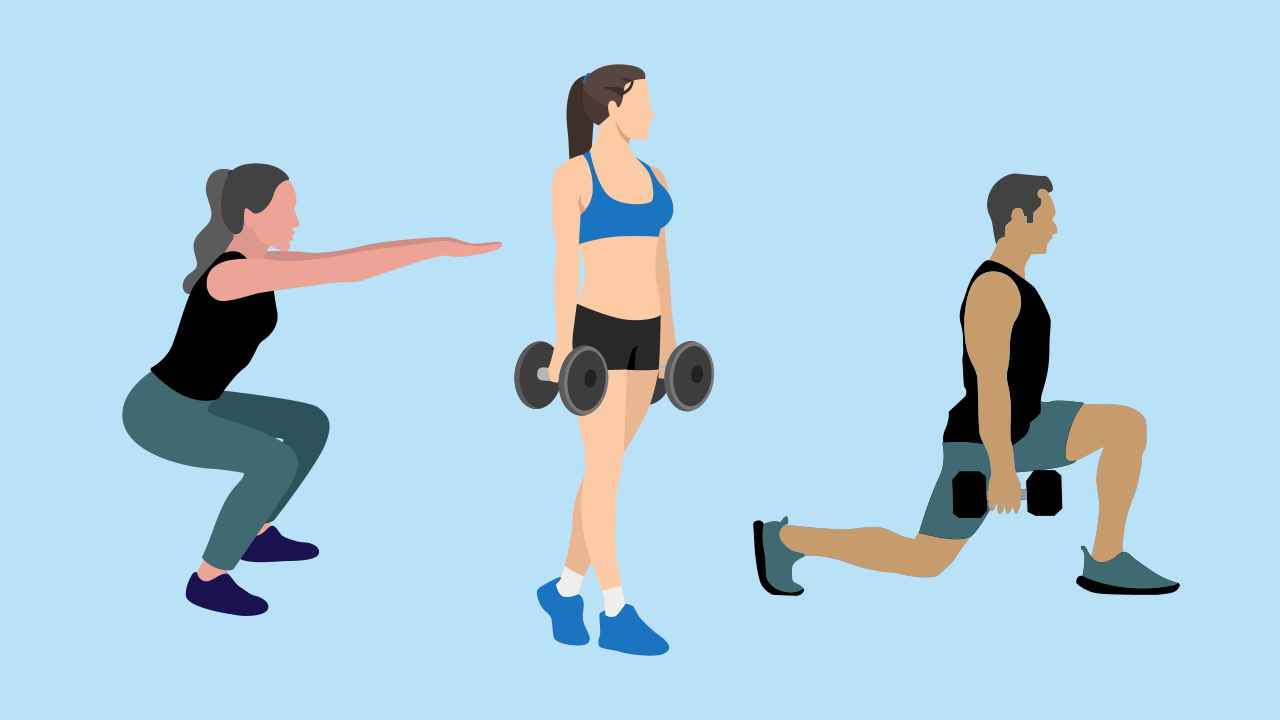

- Include compound movements, and single-joint exercises

- Perform compound (multi-joint movements) before single-joint exercises. For example: performing squats before seated knee extension. Train bigger muscles before smaller muscle groups.

Recommendations for progression during strength training

- Training intensity, volume, and rest for:

- Beginners 60%-70%. 1 – 3 sets of 8-12 reps. Rest 1-2 minutes

- Intermediate 70%-80%. Multi sets of 6 – 12 reps. Rest 2-3 minutes

- Advanced 70%-100%. Multi sets of 6 – 12 reps. Rest up to 3 minutes

- Training frequency for:

- Beginners 2-3 days per week

- Intermediate 2-4 days per week

- Advanced 4-6 days per week

Recommendations for progression during hypertrophy training

- Training intensity, volume, and rest for:

- Beginners 60%-70%. 1 – 3 sets of 8 – 12 reps. Rest 1-2 minutes

- Intermediate 70%-80%. Multiple sets of 6 – 12 reps. Rest 1 – 2 minutes

- Advanced 70%-100%. Multiple sets of 6 – 12 reps. Majority of training within 70%-85% of 1RM, 6 – 12 reps. Rest 2 – 3 minutes for high intensity, and 1 – 2 minutes for low intensity

- Training frequency for:

- Beginners 2 – 3 days per week

- Intermediate 2 – 4 days per week

- Advanced 4 – 6 days per week

Recommendations for progression during endurance training

- Training intensity, volume, and rest for:

- Beginners 50%-70%. 1-3 sets of 10-15 reps. Rest 1-2 minutes

- Intermediate 50% – 70%. Multiple sets of 10 – 15 reps. Rest 1 – 2 minutes

- Advanced 30% – 80%. Multiple sets of 10 – 25 reps. Rest: 1 – 2 min for high reps. And 1 min for low reps

- Training frequency for:

- Beginners 2 – 3 days per week

- Intermediate 2 – 4 days per week

- Advanced 4 – 6 days per week

Recommendations for progression during power training

- Training intensity, volume, and rest for:

- Beginners 60%-70% for strength. 30%-60 % for velocity and technical work. 1 – 3 sets of 6-12 reps. Rest: 2-3 minutes

- Intermediate 70%-80% for strength. 30%-60% for velocity and technical work. Multiple sets of 6-12 reps. Rest 2-3 minutes

- Advanced 80% for strength. 30%-60% for velocity and technical work. Multiple sets of 6 – 12 reps. Rest: 3 minutes for high intensity, and 1 – 2 minutes for low intensity

- Training frequency for:

- Beginners 2 – 3 days per week

- Intermediate 2 – 4 days per week

- Advanced 4 – 6 days per week

Also read: Tracking Your Fitness: Why and How Should You Do It?

You can use this as a guideline for varied goals, and make sure that progression is always a part of your training. Going by the feel might bring you results in the short-term; however, if you want to make long-term gains, and ensure improvements in your performance, an element of progression is a must in your training plan.

References

1. Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA. Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004; 36: 674-88.

2. Kirby T, Erickson T, McBride J. Model for Progression of Strength, Power, and Speed Training. Strength & Conditioning Journal 2010; 32: 86-90.

3. Boyle M. Functional training for sports. Champaign (Ill.): Human Kinetics, 2004.

4. Wade S, Pope Z, Simonson S. How Prepared Are College Freshmen Athletes for the Rigors of College Strength and Conditioning? A Survey of College Strength and Conditioning Coaches. J Strength Cond Res 2014; 28: 2746-53.

5. Baechle T. Essentials of strength training and conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2016.